The DVF Framework represents one of the most practical and powerful tools for evaluating whether an idea, product, or business initiative has genuine potential for success. Standing for Desirability, Viability, and Feasibility, this framework originated from the design thinking methodology developed at IDEO and Stanford’s d.school. It provides a comprehensive lens through which entrepreneurs, product managers, and business leaders can assess opportunities before committing significant resources.

Understanding the Three Core Dimensions

1. Desirability: The Human-Centered Dimension

Desirability addresses whether people actually want or need what you’re proposing to create. This goes beyond surface-level interest to examine genuine pain points, unmet needs, and emotional drivers that would compel someone to adopt your solution. The desirability dimension requires deep empathy and customer understanding, moving past assumptions to validate actual demand through research, interviews, observation, and behavioral data.

Many innovations fail not because they lack technical merit or business potential, but because they solve problems that don’t truly matter to customers. The desirability lens forces you to answer critical questions: What problem are you solving? For whom? How acute is this problem? What alternatives currently exist? Why would someone choose your solution over existing options or doing nothing at all?

Validating desirability requires moving beyond asking people if they like your idea. Instead, focus on understanding their current behaviors, frustrations, and workflows. Observe how they currently solve the problem. Identify what they’re already paying for or investing time in. Look for evidence of genuine demand rather than polite interest.

2. Viability: The Business Model Dimension

Viability examines whether your solution can form the basis of a sustainable business. This encompasses pricing strategy, cost structure, revenue models, market size, customer acquisition economics, competitive dynamics, and long-term financial sustainability. An idea might be deeply desirable and technically feasible, but if the unit economics don’t work or the market is too small, it won’t succeed as a business.

The viability assessment requires rigorous financial modeling and market analysis. What will it cost to acquire each customer? How much will they pay? What are your variable and fixed costs? What margins can you achieve? How long will customers remain? What’s your path to profitability? These questions force uncomfortable honesty about whether desire translates into willingness to pay, and whether that payment can support a viable business.

Viability also considers competitive positioning and market dynamics. You might have a profitable business model in theory, but if you’re entering a mature market dominated by well-funded competitors with significant advantages, viability becomes questionable. Conversely, identifying underserved niches or creating entirely new categories can strengthen viability even with higher costs or lower initial margins.

3. Feasibility: The Execution Dimension

Feasibility addresses whether you can actually build and deliver what you’re proposing given current constraints, resources, capabilities, and technology. This includes technical feasibility, operational capability, resource availability, regulatory environment, and time-to-market considerations. Many compelling ideas with clear market demand fail because they’re simply beyond the reach of the team or organization attempting to execute them.

The feasibility evaluation requires honest assessment of your capabilities and constraints. Do you have the necessary technical expertise? Can you acquire it through hiring or partnerships? Is the required technology mature enough? Do you have sufficient capital to reach key milestones? Can you navigate regulatory requirements? How long will development take, and can you sustain operations during that period?

Feasibility also encompasses operational and scaling considerations. You might be able to build a prototype or serve initial customers, but can you scale to hundreds or thousands of customers while maintaining quality? Do your processes allow for growth, or are they inherently limited? Understanding these constraints early prevents investing in ideas that can’t ultimately scale to viable business size.

The Power of Convergence

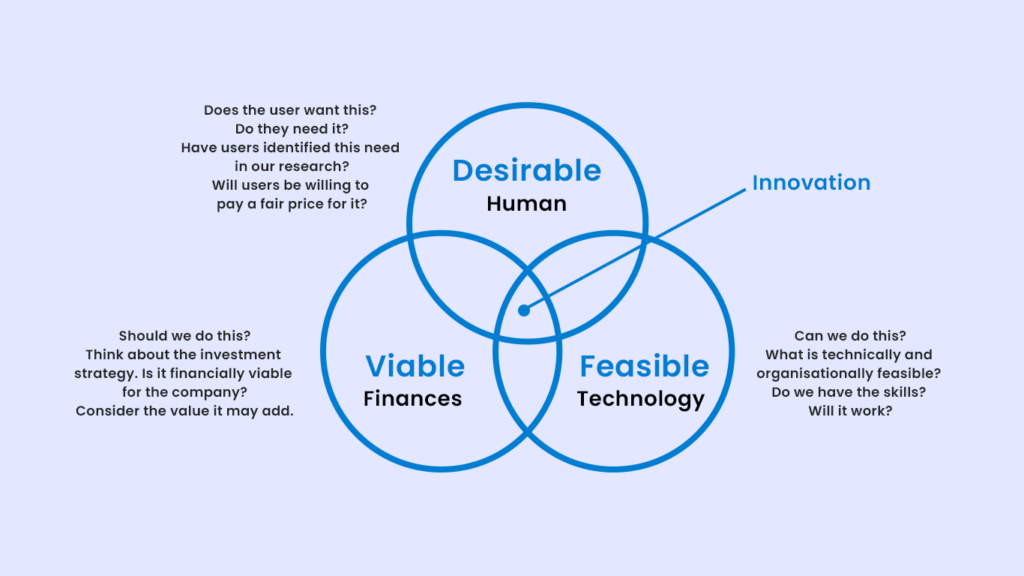

The true value of the DVF Framework emerges at the intersection of all three dimensions. Visualizing this as a Venn diagram, the sweet spot exists where desirability, viability, and feasibility overlap. This convergence point represents ideas that people want, that can be built into profitable businesses, and that you can actually execute on with available resources.

Most ideas fulfill only one or two dimensions. Technical teams often develop feasible solutions that lack market desirability or business viability. Marketing-oriented organizations sometimes identify desirable opportunities without considering feasibility constraints or viable business models. Finance-driven companies may pursue viable markets without the capabilities to feasibly compete or the insight to create genuinely desirable products.

Successful innovation requires balancing all three perspectives simultaneously. This typically demands cross-functional collaboration, bringing together diverse viewpoints to challenge assumptions and identify blind spots. The designer advocates for desirability, ensuring human needs remain central. The business strategist defends viability, maintaining focus on sustainable economics. The technical leader champions feasibility, grounding discussions in operational reality.

Conclusion

The DVF Framework provides a deceptively simple yet profoundly powerful structure for evaluating innovation opportunities. By demanding simultaneous consideration of desirability, viability, and feasibility, it prevents the single-dimensional thinking that dooms many initiatives. The framework forces difficult questions, surfaces hidden assumptions, and highlights critical gaps before they become expensive failures.

Yet the framework’s real power extends beyond initial evaluation. It serves as an ongoing navigation tool, helping organizations adapt as conditions evolve and new information emerges. Markets shift, technologies mature, customer preferences change, and competitive landscapes transform. Regularly reassessing DVF alignment ensures that yesterday’s winning strategy doesn’t become tomorrow’s obsolete approach. The framework creates a shared language across functions, enabling designers, business leaders, and technical teams to collaborate effectively around what matters most.

Success requires more than identifying a good idea. It demands finding the rare convergence where human desire meets economic viability and executable capability. The DVF Framework illuminates this intersection, transforming innovation from hopeful guesswork into strategic discipline. Those who master this framework don’t just generate better ideas. They consistently identify which ideas deserve investment, how to refine them for greater impact, and when to pivot or persist based on evidence rather than emotion. In an environment where most innovations fail, this systematic approach to validation and iteration represents perhaps the most valuable competitive advantage an organization can develop.